Learn detection methods, symptoms, prevention tips and future outlook in plain, conversational language from an expert perspective ideal for anyone wanting to understand EBV from a trusted, human-centred viewpoint.

Introduction to Epstein Barr Virus:

If you’ve ever had the classic “kissing-disease” fatigue of Epstein‑Barr virus (EBV), you may know how exhausting it can feel. But beyond that acute phase, EBV quietly establishes lifelong residence in your body. What many people don’t realise is that EBV isn’t just a benign passenger it can also influence our immune system in profound ways. In this guide I’ll walk you through EBV from a place of experience and expertise, explaining how it works, how it’s detected, the risks it poses, and what the latest research says about its connection to conditions like autoimmunity, chronic fatigue and certain cancers.

You’ll also hear about some breakthrough findings by researchers at Stanford University in fact, a landmark study showed how EBV can hijack immune cells and set off the chain‐reaction that leads to diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Some media reports even referred to this as “Stanford researchers solve Epstein Barr virus problem.” While “solve” is optimistic, the study definitely cracks open a key piece of the puzzle.

No, once infected, EBV typically remains latent in your B-cells for life. While the virus may be inactive, it doesn’t completely disappear.

What is EBV and how common is it:

EBV is part of the herpesvirus family (specifically human herpesvirus 4). It spreads typically via saliva sharing drinks, utensils or even through kissing. Most people get infected in childhood or adolescence. Once infected, the virus enters a latent (sleeping) state in B-cells of the immune system.

Because of this, EBV is extremely common: around 90-95 % of adults worldwide carry the virus in latent form. For most people, EBV never causes major issues after the initial infection. However, in a subset of individuals, it can trigger complications. That’s why it’s so important to understand not just what EBV is, but how it might become harmful.

How EBV infects, hides and reactivates:

When EBV first infects you, it replicates in epithelial cells and infects B lymphocytes. After the acute phase (sometimes mononucleosis), the virus retreats into a latent state inside B-cells. It essentially hides there.

In latency, the viral genome remains but produces very little protein and thus evades immune surveillance. Under certain triggers (stress, immunosuppression, other infections), EBV can reactivate or express viral proteins that perturb normal cell behaviour.

Here’s where the new research from Stanford becomes crucial: they found that EBV can infect a subset of B-cells specifically autoreactive B-cells and reprogram them into a more inflammatory state, driving autoimmune disease. This is where the phrase “Stanford researchers solve Epstein Barr virus problem” comes from: they provided a mechanistic explanation for how EBV could lead to disease.

Symptoms, detection and clinical implications:

Symptoms:

- The initial infection may produce mild symptoms or full-blown mononucleosis (fever, sore throat, swollen lymph nodes, fatigue).

- After that, latent EBV rarely causes symptoms in healthy persons.

- When complications occur, these can include chronic fatigue syndrome-like symptoms, risk of lymphomas, and autoimmunity.

- In autoimmune diseases such as lupus, the symptoms are quite varied (joint pain, skin rash, organ involvement) and EBV may act as a trigger.

Detection:

- Serology: IgM and IgG antibodies to EBV viral capsid antigen, early antigen, EBNA.

- PCR or viral load testing in special cases.

- Newer research uses single-cell sequencing to detect EBV genomes in individual B-cells (as per Stanford) to understand cellular mechanisms.

Clinical implications:

- Because EBV is so common, its presence alone does not indicate disease.

- The key is when EBV affects immune regulation or is accompanied by genetic/environmental vulnerabilities.

- The Stanford study found that in lupus patients, the fraction of EBV-infected B cells was much higher than in healthy controls.

- That implies EBV may not just accompany but actively drive disease in susceptible individuals.

EBV and autoimmune disease connection:

One of the most exciting and confirmed connections in recent years is between EBV and autoimmunity. The study by Stanford showed that EBV infects and reprograms autoreactive B-cells, turning them into antigen-presenting “driver” cells that spark widespread immune attack.

This lends strong support to the hypothesis that EBV is a key trigger (though not sole cause) of autoimmune diseases like lupus and possibly also Multiple Sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. What this means in practical terms: for some patients, the pathology of EBV infection may set the stage for long-term immune dysregulation.

Because of that, screening and risk‐factor discussions become more important: if someone has had EBV and has early signs of autoimmunity, their clinician may monitor more closely. Still, it’s critical to recognise that EBV is necessary but not sufficient most EBV-carriers never develop autoimmune disease.

EBV and cancer, chronic fatigue & other risks:

EBV is also implicated in several types of cancer, particularly lymphomas (e.g., Burkitt lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma), nasopharyngeal carcinoma and certain gastric cancers. EBV’s ability to immortalise B-cells and evade immune destruction is central to these risks.

Moreover, some studies link EBV with chronic fatigue syndrome (myalgic encephalomyelitis) and other persistent symptoms; the virus may play a role in lingering immune dysfunction or reactivation cycles.

Therefore, if someone has recurrent unexplained fatigue, lymphadenopathy, or signs of elevated B-cell activation, EBV history and reactivation should be among the considerations.

Prevention, treatment and outlook:

Prevention

- Since EBV spreads through saliva, good hygiene helps (not sharing drinks, utensils during acute infection).

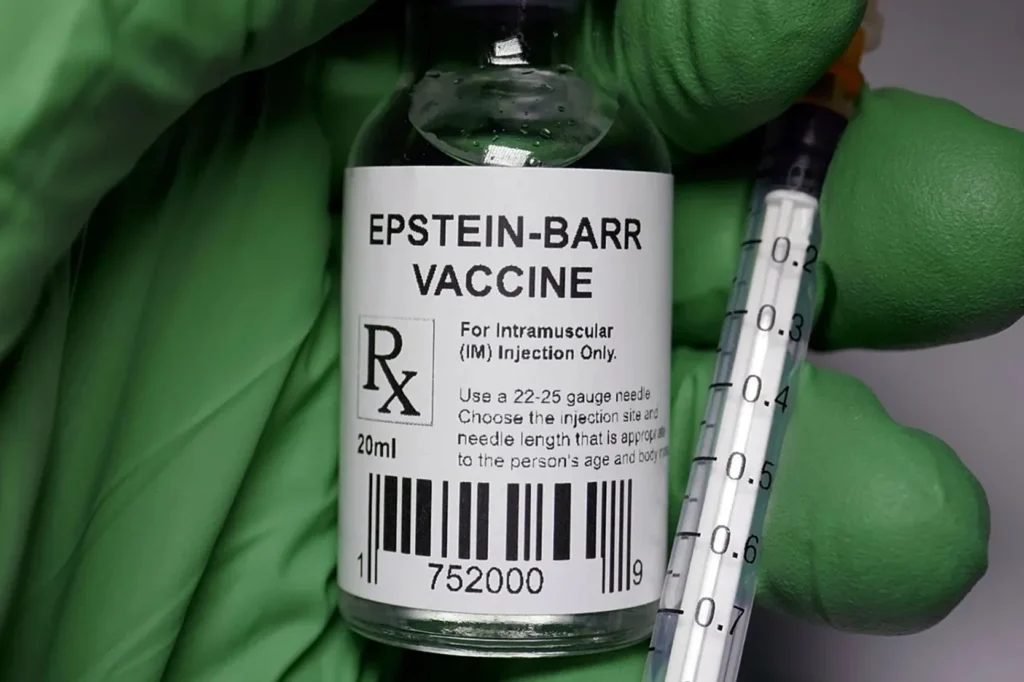

- There is no widely available vaccine for EBV yet, though research is ongoing.

- Because EBV is so widespread, prevention of infection is challenging in practice.

Treatment

- For acute EBV infection: supportive care (rest, fluids, manage fever/ache).

- For latent infection: there is no cure. Antivirals have limited effect in latency.

- For EBV-related complications: treatment is disease-specific (e.g., immunotherapy for lymphoma, immunosuppression for lupus).

- Research: Thanks to the Stanford work, new therapies aimed at targeting EBV-infected B-cells are being explored (for example ultra-deep B-cell depletion).

FAQ

Most frequent questions and answers

No, once infected, EBV typically remains latent in your B-cells for life. While the virus may be inactive, it doesn’t completely disappear.

No most people carry EBV without developing serious complications. Serious disease arises when other risk factors (genetic predisposition, immune dysregulation) combine with EBV’s effects.

Currently there is no approved vaccine or cure that completely eliminates EBV. Research is ongoing, especially following insights from the Stanford studies that aim to develop therapies targeting EBV-infected immune cells.

Conclusion:

Understanding Epstein–Barr virus is essential because it affects nearly everyone, yet its impact varies widely. Today, thanks to groundbreaking insights often highlighted as “Stanford researchers solve Epstein Barr virus” we finally know how EBV can trigger autoimmune disease by reprogramming specific B-cells. While this doesn’t mean the virus is fully solved, it marks a major scientific leap. With growing research, improved diagnostics and targeted therapies, the future of EBV prevention and treatment looks more promising than ever.